Blades of Fire on PC

If you’d asked me what I thought MercurySteam would move on to after releasing the impeccable Metroid Dread in 2021, the answer would not have been anything close to what Blades of Fire is.

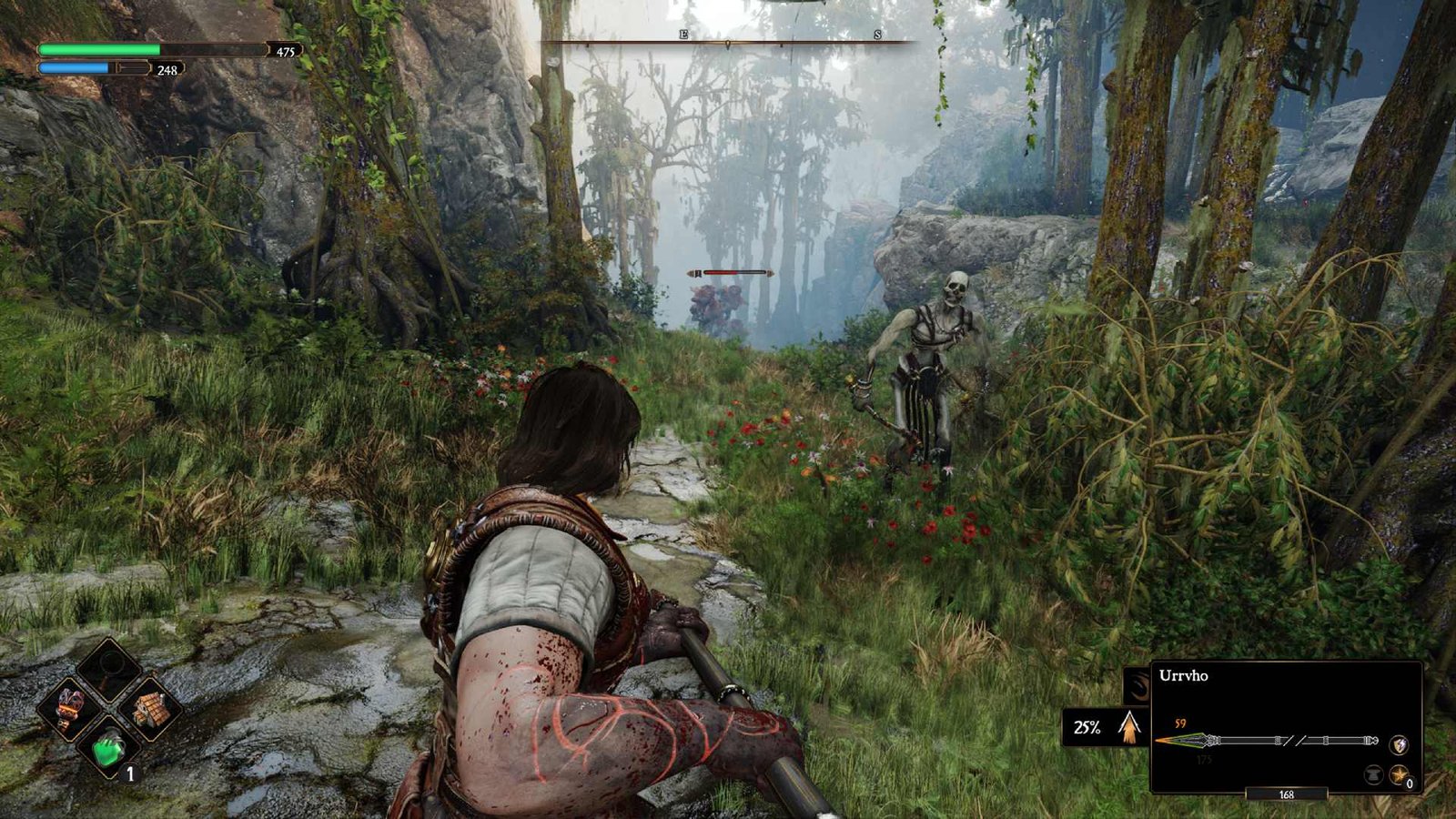

Published by 505 Games, this is a third-person action game with Souls elements and a combat system unlike anything the studio had previously done, giving shape to one of the strangest games I’ve played this year. It’s filled with unique ideas and distinct mechanics, but much of it fails to come together as a cohesive whole, making for a messy and disjointed experience.

The premise and world of Blades of Fire is one area MercurySteam has a firm grasp on. Set in a world formerly ruled by a race of giants known as The Forgers, the calculating Queen Nerea has cast a spell that turns her enemies’ steel to stone.

It isn’t far off to describe this act as sacrilegious, given the general population’s reverence for The Forgers, as her curse twists their legacy against humanity. She exerts her pressure on the world and all those who occupy it, enforcing authoritarian rule. It falls to Aran De Lira, our protagonist, to kill Queen Nerea and bring an end to her tyranny.

Blessed at the beginning of the game by The Forgers themselves, Aran De Lira is a likeable everyman. Someone who isn’t afraid to put his own life on the line for the sake of others. The Forgers entrust him with one of The Seven Hammers; primordial tools that created the beginnings of the human era. It’s with this hammer that Aran De Lira can forge his own arsenal as he journeys across the lands towards the Royal Palace.

It’s a standard setup, but differentiates itself in how well-realised and thought-out this world is. Middling characters aside, the world that MercurySteam has created here is rich with ideas, lore, and history to uncover as you play. None of it is overtly signposted or forced down your throat via exposition, either. It’s not too dissimilar to what a Dark Souls game does with narrative, only Blades of Fire is a bit more hands-on and gives with its information if you seek it out.

The narrative that surrounds it all is less arresting, though. It has its moments, but it doesn’t feel like Aran goes through much development for the majority of the game. The same can be said for his companion, Adso, who can even be sent back to camp mid-exploration if you don’t want him around. It does have some revelations towards the end of the game that make it a little more worthwhile, but it simply didn’t grab me in the way the world did in its opening hours.

Where MercurySteam takes the biggest swings with Blades of Fire, is undoubtedly in its gameplay systems. It’s a strange mix of popular design elements from Souls-like games and some rather unorthodox mechanics that do fit within the kind of game Blades of Fire is trying to be. You’ll venture throughout different areas, battling enemies and bosses, finding Forges along the way that you respawn at when you die. Enemies also respawn on death, and Forges can be used to fast-travel between one another, repair damaged weapons, and most importantly, forge new ones.

Blades of Fire’s entire loop is built around the forging and maintaining of new armaments. Defeating enemies and exploring the world will net you resources, specifically steel, timber, and monster parts to use in forging. You’ll initially start with one weapon type you can forge, slowly unlocking more as you defeat enemies that specialise in other instruments of death. You customise how your weapon will turn out, from handle sizes and blade shapes, to what kind of pommel you want on your hilt. It’s a flexible and fun system, punctuated by a smithing minigame to temper your freshly forged equipment to last longer.

I say last longer because none of these weapons are permanent. Efficient tempering and blade shaping will allow you to repair your forged weapon a set number of times, but once all have been used and your durability depletes, a weapon is rendered useless. You can then recycle them for parts or dispose of them in other ways, but it means you’re constantly crafting new weapons of different types to ensure you always have something on you.

This is reinforced by general combat, where enemies have weaknesses and resistances to specific weapons and damage types depending on their armour or body structure. Queen Nerea’s armoured soldiers, for example, are much more susceptible to blunt damage, making hammers suitable for the occasions they pop up. Something a bit more fleshy might struggle withstanding attacks from great swords and spears. It behoves you to carry a little bit of everything at once to be equipped for all situations.

Some weapon classes even have stances, with their own damage modifiers and efficiency against different enemy types. If the emphasis on managing your own weaponry isn’t obvious enough, the final nail in the coffin is undoubtedly the fact that you drop your equipped weapon on death. It’s a genuinely great system that always had me excited to discover new materials or a unique weapon type to forge, and experimenting with the different aspects of your weapons to find what works best for your desired combat style is engaging.

I do wish that this system had more of an impact on combat, though. You can attack from all four directions, left, right, up, and down. When you lock onto an enemy, a brief outline will show how effective your current weapon is against the different areas of their body, typically informing what kinds of combos you’ll want to utilise in your skirmishes. It isn’t too far from For Honor in this regard, and is fun to play around with at first. Unfortunately, it just doesn’t stay engaging for the entire runtime of Blades of Fire. It eventually devolves into managing stamina, and much of the puzzle involved with how you target an enemy is solved for you the moment you lock onto a target.

Additionally, all of this is poorly explained in Blades of Fire’s opening hours. It gets the basics across just fine, but its most nuanced and vital details aren’t adequately explained and require you to dig through menus or tutorials to understand how they fit into combat fully. The same can be said of forging weapons, which presents you with lists of unexplained stats, modifiers, and values that overwhelm instead of pique your interest.

Perhaps most surprising is that level design is a frequent frustration. It’s labyrinthine and confusing in all the wrong ways, with poorly marked points of progression, samey environments, and a map that only serves to exacerbate how lost you are at times. I love a good interconnected world, but so many of Blades of Fire’s key locales were not fun to traverse in the way that MercurySteam have always been fantastic at.

Another area that MercurySteam delivers, though, is in production values. Developed in their own proprietary Mercury Engine 6, Blades of Fire runs and looks phenomenal for the duration of its runtime. It performs without skipping a beat, which is key for a game with combat like this. The visuals are straight out of the seventh generation of consoles in the best possible way, with a bright and gaudy colour palette fit for a fantasy world of this kind.

So much of the reason that this is a resounding success here is again thanks to MercurySteam’s realisation of this world. It comes through in the art design for its enemies, environments, and characters. From the creaky red wood of the Crimson Fort to the spectral glows of the Doyen Graves, Blades of Fire is always a treat to look at. It had me excited to see what new designs lay in wait for me around the next corner.

There are many parts of Blades of Fire that I admire or had fun with. It’s unique and inventive in ways that so many games aren’t nowadays. Unfortunately, its many moving parts fail to come together and create a cohesive whole. It’s far from being an outright terrible game, but it doesn’t come close to the highs that MercurySteam have been able to achieve with their other titles in recent years.

Blades of Fire is launching on May 22nd for PC, PS5, and Xbox Series X|S.

SavePoint Score

Summary

While Blades of Fire brings fresh and engaging systems to the table, it struggles to forge a true connection when it matters the most.